History and Biodiversity of Robusta

Coffee is one of the most important cash crops in the world, generating significant foreign exchange and supporting the livelihoods of millions of people globally. Over the last 30 years, demand for coffee has grown steadily, leading to an expansion in production and exports.

There are 131 species in the Coffea genus known to science, with two that are cultivated widely and on a global scale —Coffea arabica (commercially known as arabica) and Coffea canephora (commercially known as Robusta). Throughout this essay and the catalog generally, we use this term “Robusta” to refer to the entire C. canephora species and all its subtypes.

Our coffee is facing risks due to climate change, low productivity, diseases, and limited access to good seed sources for farmers. As a consequence, the livelihoods of coffee farmers are also being affected. | Photo: WCR

Until recently, arabica held reign over most of the coffee market due to preferences for its cup quality, but various factors, including the increasing demand for coffee, have led to expansions in the production of Robusta, as the species requires less stringent growing conditions and possesses a certain level of resistance to pests and diseases that often plague farm productivity. Robusta production expanded rapidly after the emergence of soluble coffee in the 1950s.

Currently, approximately 60% of the world’s coffee production and sales come from Arabica coffee plants, while 40% is from Robusta coffee plants.

(Source: ICO, 2021)

The top global producers of Robusta are currently Vietnam, Brazil, Indonesia, Uganda, and India, which together produce over 90% of the world’s Robusta. Of these producers, Vietnam and Uganda are the foremost exporters of Robusta (Brazil, for example, retains a substantial portion of its production for internal consumption). However, an increasing number of countries that currently restrict or have previously restricted coffee production to arabica are beginning to explore Robusta; these include Mexico, Nicaragua, Guatemala, and Colombia, among others. Additionally, there is growing interest in exploring the potential of increasing the cup quality of Robusta.

About Robusta

The interest in producing Robusta at a global level resides in the fact that it can be grown in a wider range of climates and altitudes compared to arabica, which requires precise conditions in order to thrive, like heavy shade and high altitudes. In contrast to arabica, Robusta plants typically have a greater crop yield, contain higher levels of caffeine, lower levels of sugar, higher levels of soluble solids, and are less susceptible to damaging pests and diseases. Further, Robusta can be grown in hotter, more humid temperature ranges, found in lower altitudes between 200 – 800 meters, and often requires less maintenance via herbicide and pesticide.

Despite these attributes, Robusta is still sensitive to environmental disturbances. Research suggests that Robusta’s ability to thrive in hotter climates may be overstated and that temperatures over 20.5 degrees centigrade can have a significant negative impact on yields Kath. Additionally, many Robusta varieties are still susceptible to key diseases and pests, such as coffee leaf rust, stem borer, coffee berry disease, coffee berry borer, and nematodes, among others.

Robusta coffee is often easier to cultivate, leading to higher yields and greater efficiency compared to Arabica coffee. Climate forecasts for the year 2050, provided by the World Coffee Research organization, indicate that rising temperatures and changing rainfall patterns could make Arabica coffee cultivation unsustainable in the coming years, potentially leading to a significant increase in Robusta coffee production. However, Robusta coffee also faces its own limitations and vulnerabilities due to its climate.

However, the beans that come from Robusta production generate differences in terms of taste and cup quality. For instance, coffee brewed from Robusta beans is often lower in acidity, higher in bitterness, and more “full-bodied” due to its pyrazine content, an aromatic known for its earthiness. But when handled and processed properly, Robusta can serve as a product for specialty markets.

Robusta Diversity

Many different common terms are used to describe Robusta in the areas where it is grown. These include “Robusta,” “conilon,” “nganda,” “koillou/quillou,” and others. These terms are generally regional, colloquial, and do not necessarily correspond to specific genetically distinct varieties/clones that have been developed and released by breeders over the years.

Because Robusta is a cross-pollination crop – a single Robusta plant cannot efficiently pollinate its own flowers (unlike Arabica coffee, which can do so); scientists call this “Allogamous.” Therefore, individuals planted on the same farm often cross-pollinate with each other. The consequence of this pollination system is that a significant portion of Robusta coffee is produced from populations that are not selectively bred, as they are derived from freely pollinated seeds.

In simple terms, Robusta coffee plantations are genetically heterogeneous; therefore, many farmers growing Robusta coffee often have little awareness of the specific variety or subspecies they are cultivating. This is why C. canephora is commonly referred to simply as “Robusta” in the commercial context, starting around 1900.

As Robusta coffee is a cross-pollination species (meaning it requires pollen from two different plants to create new fruit), farmers need to plant more than one type of Robusta coffee on their farm to achieve efficient yields. Some breeding programs have been developed to create “multi-line varieties,” aimed at purposefully blending genetically diverse inbred lines.

In different coffee-producing regions, these mixed varieties are distributed to farmers in various ways. For example, in West Africa, breeders often create multi-line varieties (meaning different Robusta coffee types are distributed together in the same seed package for farmers). In Brazil, breeders typically produce multiple individual inbred lines and then test their compatibility; the inbred lines with the highest productivity are then propagated and supplied to farmers.

However, not all Robusta varieties can cross-pollinate with each other – their cross-compatibility is genetically controlled. Some varieties cannot fertilize each other. Until now, research on the optimal combination of subspecies in production remains scarce, but one crucial factor to consider is synchronous flowering.

The genetic diversity of Robusta coffee is much larger compared to Arabica coffee. There are many unknown variants (including characteristics related to coffee quality) within the genetic pool of Robusta coffee. Overall, these hidden variants have not been explored by breeders.

According to WCR (World Coffee Research),

History of cultivation & dispersal

The cultivation of this species began around 1870 in Congo, with the seed source taken from the Lomami River region of what is now the Democratic Republic of the Congo. A subspecies of Robusta, known as “kouillou” (later renamed “conilon” due to linguistic changes upon importation to Brazil), was discovered in the wild by the French in 1880, mainly along the Kouilou-Nari River area between Gabon and the mouth of the Congo River. This species was named Coffea canephora by the botanist Louis Pierre in 1895.

Pierre (full name Jean Baptiste Louis Pierre) was a renowned French botanist known for his studies in Asia (he was in charge of the Saigon Zoological Garden from 1865 to 1877). During his time at the French National Museum of Natural History, he received a plant sample collected by Reverend Théophile Klaine in Gabon and named it Coffea canephora. This name was first published along with a species description by Wilhelm Froehner, a historian, in 1897.

In 1898, Edouard Luja, a biologist, researcher, and explorer, was sent to collect 10 economically potential species in Congo in preparation for the Paris 1900 Exhibition. During this mission, Edouard Luja collected several thousand seeds of a “new” coffee species in the Lusambo area (now part of the Democratic Republic of the Congo). These seeds might have been collected from an early Robusta coffee plantation in the region. The Democratic Republic of the Congo became one of the main distribution centers, from which coffee varieties spread throughout tropical regions.

In the early 20th century, this species began to spread to other parts of the world. Robusta seeds from Congo were sent to Brussels, Belgium (during its colonial period), and from there, they were sent to Java, Indonesia, where it was quickly embraced by farmers due to its high yields and resistance to coffee leaf rust, which had caused a major outbreak in Southeast Asia in the late 1800s. From this original variety, the name “Robusta” was later supplemented with new genetic sources from Gabon and Uganda. During the same period, other Robusta coffee types were selected from wild coffee populations and introduced to regions in Ivory Coast, Guinea, and Uganda.

From there, Robusta coffee continued its global expansion, initially reaching India through seeds from Java, Indonesia, and later being imported from West Africa. Selected Robusta coffee plants from Java were reintroduced to Central Africa starting in 1910 and reached the Belgian Congo in 1916, where the National Agricultural Research Institute of Congo (INEAC) played a crucial role in breeding programs’ development from 1930 to 1960. In Africa, Robusta coffee production expanded to Madagascar, Uganda, Ghana, and Ivory Coast, often blending native variants with variants introduced from commercial production in other regions of the continent. The significant driver behind the dissemination of Robusta coffee during this period was the spread of coffee leaf rust disease.

Robusta coffee plants were subsequently imported into Latin America, particularly Brazil, and Central America through Guatemala between 1930 and 1935. Moreover, the Tropical Agricultural Research and Higher Education Center (CATIE) in Costa Rica introduced Robusta coffee known as “French lines” around 1981-1983.

Today, countries in Asia and the Pacific are the largest producers of Robusta coffee, accounting for 60% of the world’s production at approximately 41.5 million 60 kg bags per year. Following this region is South America, contributing 28% of the world’s Robusta coffee market share, producing around 19.8 million bags in the 2020-2021 crop year.

ICO, 2022

Genetic diversity and conservation

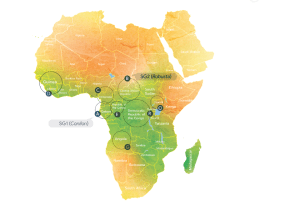

C. canephora is a diploid species (2n = 2x = 22) divided into two major genetic groups, Guinean and Congo. The Guinean group originates from West Central Africa, while the Congo group originates from Central Africa. Among these two groups, the Guinean group is the most widespread. Additionally, within each group, there are different populations or subgroups. In the Guinean group, there are at least two subgroups named “kouilou” or “conilon” and “robusta”. However, recent studies using advanced genetic techniques have further classified the C. canephora coffee species into 5 genetic groups (A, B, C, D, and E).

Robusta is commonly divided into two major genetic groups: the Congo group and the Guinean group; each group is distinguished by differences in growth morphology and adaptation to different ecological conditions.

Geographically, genetic group A includes wild populations from Congo and Cameroon; group B from East-Central Africa; group C from West-Central Africa, Cameroon, and northeastern Congo; group E from Congo and southern Cameroon; while group D consists of wild populations from Côte d’Ivoire (Ivory Coast) and Guinea. Additionally, some wild populations in Uganda form a separate group (group O). Finally, in 2019, some authors described the genetic diversity of C. canephora with eight distinct genetic groups, with the addition of a group from Uganda (group O), a group from southern Democratic Republic of Congo (Group R), and a group from Angola (group G), with weaker differentiation between groups E and R.

Reference: This article is compiled based on content provided by the World Coffee Research organization. You can find the original article at: History of Robusta.

- //varieties.worldcoffeeresearch.org/robusta/varieties